1. Introduction

1.1 Context: Why fraud detection systems need real-time scalability

In today’s digital economy, the speed and volume of financial transactions are constantly accelerating. From e-commerce purchases to peer-to-peer payments, billions of dollars change hands every day, often in milliseconds. This rapid pace, while beneficial for users, presents a fertile ground for sophisticated fraudsters who exploit even the smallest windows of opportunity. Traditional batch-processing fraud detection systems, which analyze transactions hours or even minutes after they occur, are increasingly obsolete. By the time an alert is raised, the fraudulent transaction has often already been completed, and the funds are long gone. The imperative for modern financial systems is clear: fraud detection must be real-time, capable of intercepting malicious activity before it impacts customers or financial institutions. Furthermore, these systems must be inherently scalable, designed to handle explosive growth in transaction volumes without compromising detection accuracy or latency.

1.2 The challenge of high-velocity financial data

Processing high-velocity financial data for fraud detection introduces a unique set of engineering challenges. Beyond the sheer volume of data, the data itself is often disparate, originating from various sources such as payment gateways, user behavior logs, and third-party risk scores. Each data point needs to be ingested, processed, and analyzed with minimal delay to inform a fraud decision within sub-second timeframes. This requires:

- Ultra-low latency: Decisions must be made in milliseconds to prevent fraudulent transactions from completing.

- High throughput: The system must comfortably handle tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of transactions per second.

- Data consistency: Maintaining an accurate and up-to-date view of user and merchant activity across a distributed system is crucial.

- Resilience and fault tolerance: Any disruption can have significant financial consequences, demanding a system that is robust against failures.

- Dynamic adaptability: Fraud patterns evolve rapidly, necessitating a system that can quickly incorporate new rules or machine learning models.

1.3 Introducing FraudShield: a modular microservice-based architecture

FraudShield is engineered to meet these exacting demands through a modular, microservice-based architecture. Recognizing the limitations of monolithic systems in high-velocity environments, FraudShield adopts an event-driven paradigm that promotes loose coupling, independent scalability, and enhanced fault isolation. Each core function — from payment ingestion to fraud decisioning and data storage — is encapsulated within its own service, communicating asynchronously via a robust message broker. This design ensures that components can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently, providing the agility necessary to combat evolving fraud threats.

1.4 Target workload: 20,000 payment requests per minute

To demonstrate its capabilities, FraudShield is specifically designed and optimized to process a target workload of 20,000 payment requests per minute, equating to approximately 333 transactions per second. This benchmark represents a significant volume characteristic of medium-to-large scale payment processors and fintech platforms, making it a realistic and challenging target for real-time fraud detection. Achieving this throughput requires meticulous attention to every layer of the architecture, from efficient API design to highly optimized data pipelines and rule engines.

1.5 Overview of what this article covers

This article will meticulously deconstruct the design and implementation of FraudShield. We will begin by outlining the core problem statement and defining the key design objectives. Subsequently, we will present a high-level architectural overview, illustrating the data flow and the rationale behind an event-driven approach. A deep dive into each critical component—the API Gateway, Message Broker, Fraud Detection Service, and Data Storage—will follow, detailing their specific roles, technologies, and optimization strategies. The discussion will then progress to low-level design considerations, horizontal scaling strategies for the target workload, performance optimization techniques, and a thorough examination of reliability and fault tolerance mechanisms. Finally, we will explore alternative architectural paradigms, articulate why FraudShield’s approach is optimal, and discuss future enhancements, culminating in key takeaways for designing scalable real-time fraud detection systems.

2. Problem Statement & Design Objectives

2.1 Nature of payment fraud and detection requirements

Payment fraud is a multifaceted and ever-evolving threat. It encompasses a wide range of illicit activities, including stolen card usage, account takeovers, synthetic identity fraud, friendly fraud, and money laundering. Each type of fraud leaves distinct digital footprints, requiring diverse detection mechanisms. Effective fraud detection systems must:

- Identify suspicious patterns: This includes anomalous transaction amounts, frequencies, locations, and behavioral deviations.

- Leverage diverse data points: Combining internal transaction data with external data (e.g., IP reputation, device fingerprints) is crucial.

- Operate at different granularities: Detecting fraud at the individual transaction level, but also identifying patterns across user accounts, merchants, or even entire networks.

- Minimize false positives: Incorrectly flagging legitimate transactions as fraudulent can lead to customer dissatisfaction and lost revenue.

- Adapt to new threats: Fraudsters constantly develop new tactics, demanding a system that can quickly integrate new rules, models, and detection logic.

2.2 Core challenges:

The most pressing challenge is the simultaneous requirement for high throughput (processing a massive number of transactions per second) and ultra-low latency (making a fraud decision within milliseconds). These two often conflicting requirements demand careful engineering trade-offs and highly optimized components. A system that can handle 20,000 requests per minute cannot afford any single-point bottlenecks or synchronous blocking operations.

Fraud decisions must be made in real-time, meaning before the transaction is authorized. This necessitates a system that can ingest, enrich, evaluate, and respond within a window typically under 500ms, often much less. This is in stark contrast to batch systems where decisions can take minutes or hours.

There’s an inherent tension between the accuracy of fraud detection and the performance of the system. More complex rules or machine learning models might offer higher accuracy but demand more computational resources and introduce greater latency. The design must strike a pragmatic balance, often employing a tiered approach where simpler, faster rules pre-filter transactions before more intensive analysis.

In a distributed, high-throughput system, maintaining data consistency (e.g., ensuring velocity counts are accurate across all instances) is complex. Similarly, the system must be highly fault-tolerant, designed to withstand individual component failures without losing data or impacting service availability. This means implementing mechanisms like message acknowledgments, retries, dead-letter queues, and robust data replication.

2.3 Design goals:

Given these challenges, FraudShield’s design is guided by the following core objectives:

The system must be capable of scaling out by adding more instances of services rather than scaling up existing ones. This is critical for handling fluctuating workloads and for future growth. Every component, from the API gateway to the rule engine and database, must be designed with horizontal scalability in mind.

Adopting an event-driven architecture (EDA) ensures that services are loosely coupled, communicating primarily through asynchronous messages. This decoupling enables independent development, deployment, and scaling of microservices, enhancing system resilience and agility.

A failure in one part of the system should not cascade and bring down the entire system. Microservices, combined with robust message queuing and circuit breaker patterns, contribute to isolating faults and limiting their impact.

The system must provide comprehensive observability through detailed metrics, logs, and traces. This allows for real-time monitoring of performance, quick identification of bottlenecks or failures, and proactive troubleshooting. Resilience measures, such as automatic retries, dead-letter queues, and graceful degradation, are fundamental to ensuring continuous operation.

3. System Design Overview (High-Level Architecture)

3.1 Conceptual architecture diagram (FraudShield reference)

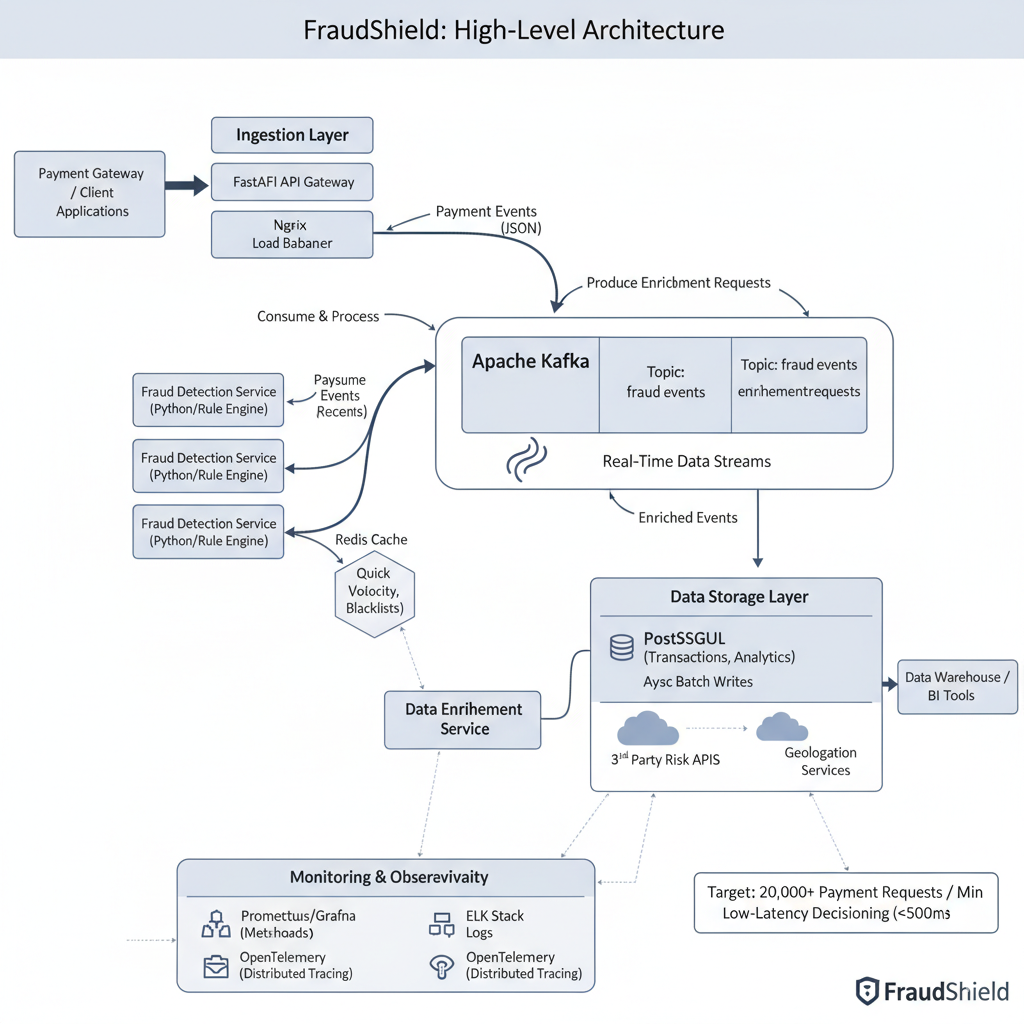

The above diagram illustrates FraudShield’s high-level architecture, designed to process and detect fraud in real-time. It showcases an event-driven flow, from initial payment request ingestion to final fraud decisioning and storage, highlighting the interplay between its core microservices.

3.2 Data flow from payment ingestion to fraud decision

The data flow within FraudShield is designed for maximum efficiency and real-time processing:

- Payment Ingestion: Client applications or payment gateways submit payment requests (JSON payload) to the API Gateway. This layer is responsible for initial validation, rate limiting, and providing idempotency guarantees.

- Event Production: Upon successful ingestion, the API Gateway immediately publishes the raw payment event to a dedicated Kafka topic (fraud-events). This hands off the processing to the asynchronous backend and ensures low latency at the ingestion point.

- Real-time Processing:

- Fraud Detection Service: Multiple instances of the Fraud Detection Service (our Rule Engine) consume fraud-eventsfrom Kafka. They perform real-time evaluations against predefined rules, leveraging Redis for quick lookups of hot data (e.g., velocity checks, blacklists).

- Data Enrichment Service: (Not explicitly shown as a primary path, but implied by ‘Enrichment Requests’ topic). This service would consume events, call third-party APIs (e.g., geolocation, IP reputation, device fingerprinting), and then publish enriched events to another Kafka topic or back to the fraud-events topic, which the Rule Engine would then consume.

- Decision & Storage: Once the Fraud Detection Service makes a decision (e.g., “approve,” “decline,” “review”), this decision, along with the processed event, is published to an “enrichment” or “decision” topic in Kafka.

- Data Persistence: A dedicated consumer (or the Fraud Detection Service itself, for simplicity in this model) persists the original transaction data and the fraud decision to the PostgreSQL database. This database serves as the primary source of truth for transactional data and historical analysis. Asynchronous batch writes are preferred to optimize database performance.

- Monitoring & Observability: Throughout this entire flow, metrics, logs, and traces are collected and sent to the Monitoring & Observability stack (Prometheus, Grafana, ELK, OpenTelemetry) for real-time insights and proactive issue detection.

3.3 Why event-driven architecture (EDA) suits fraud detection

An Event-Driven Architecture (EDA) is particularly well-suited for real-time fraud detection due to several inherent advantages:

- Decoupling: Services operate independently, reducing interdependencies and enabling separate scaling, deployment, and failure isolation. A failure in the Fraud Detection Service, for example, won’t directly halt the API Gateway.

- Scalability: Kafka’s inherent horizontal scalability allows for massive throughput. By adding more partitions and consumer instances, the system can handle virtually any volume of incoming events.

- Asynchronous Processing: Long-running or resource-intensive operations (like complex rule evaluations or external API calls for enrichment) do not block the ingestion path. This is crucial for maintaining low latency.

- Real-time Data Streams: Kafka acts as a central nervous system, providing a durable and ordered log of all events, enabling real-time stream processing and easy replayability for analysis or recovery.

- Extensibility: New services (e.g., a machine learning prediction service) can easily tap into the existing event streams without requiring changes to upstream components.

- Resilience: Kafka’s fault-tolerant design, coupled with consumer group management, ensures that events are not lost and processing can resume from the last committed offset after failures.

3.4 Core services and their roles:

The entry point for all payment requests. Implemented using FastAPI, chosen for its high performance (built on Starlette and Pydantic), asynchronous capabilities, and robust data validation features. It handles request parsing, basic validation, authentication (not detailed in diagram but a typical component), and immediately publishes valid events to Kafka. Nginx acts as a load balancer in front of multiple FastAPI instances to distribute incoming traffic.

The central nervous system of FraudShield. Apache Kafka provides a high-throughput, fault-tolerant, and durable real-time event streaming platform. It acts as the backbone, connecting all microservices and ensuring reliable, ordered, and scalable communication of payment events and fraud decisions.

The core intelligence of FraudShield. This microservice consumes payment events from Kafka, applies a set of business rules (e.g., velocity checks, blacklist lookups, geographic restrictions), and makes a fraud decision. It leverages Redis for sub-millisecond access to frequently needed data. Multiple instances of this service can run in parallel, consuming from different Kafka partitions to achieve high throughput.

- PostgreSQL: The primary relational database for persisting all transactional data, fraud decisions, and historical records. Chosen for its reliability, ACID compliance, and robust indexing capabilities. Optimized for high-volume writes (batch inserts) and analytical queries (read replicas).

- Redis: An in-memory data store used as a high-speed cache for “hot data” required by the Fraud Detection Service. This includes velocity counters, blacklisted entities, merchant thresholds, and other frequently accessed data points that demand extremely low-latency lookups.

A critical cross-cutting concern. This encompasses:

- Metrics: Collecting system performance metrics (CPU, memory, I/O, Kafka lag, service latency) using Prometheus and visualizing them via Grafana.

- Logs: Centralized logging via an ELK (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana) stack for aggregated log analysis and troubleshooting.

- Distributed Tracing: Utilizing OpenTelemetry to trace requests across multiple microservices, providing end-to-end visibility into request flow and identifying latency bottlenecks.

3.5 Latency budget and SLA targets

For a system processing 20,000 payment requests per minute, real-time decisioning is paramount. FraudShield targets a P99 latency of less than 500 milliseconds for a complete fraud decision cycle, from the moment a payment request hits the API Gateway to the point a fraud decision is available. This tight latency budget dictates several design choices:

- Asynchronous communication: All inter-service communication is asynchronous via Kafka.

- Optimized processing: Rule evaluation in the Fraud Detection Service is highly optimized, leveraging in-memory caches (Redis) to avoid costly database lookups during the critical path.

- Efficient I/O: Non-blocking I/O is used extensively, particularly in the API Gateway and Kafka consumers.

- Horizontal scaling: Rapid scaling of compute resources to match demand and prevent backlogs.

The 500ms P99 SLA means that 99% of all payment requests should receive a fraud decision within half a second. This ensures that the vast majority of transactions can be approved or declined almost instantaneously, significantly reducing the window for fraud and improving the user experience.

4. Deep Dive: Each Component Explained

4.1 Ingestion Layer (API Gateway)

The Ingestion Layer is the system’s first line of defense and the primary interface for incoming payment requests. Its design is critical for handling high throughput and ensuring reliable entry into the fraud detection pipeline. FraudShield utilizes FastAPI as its core API Gateway, fronted by a Nginx load balancer.

FastAPI is chosen for its exceptional performance, largely due to its foundation on Starlette (an asynchronous web framework) and Pydantic (for data validation).

- Asynchronous I/O (async/await): FastAPI natively supports asynchronous operations. This means that while an I/O bound task (like publishing a message to Kafka) is waiting, the server can switch to processing another incoming request instead of blocking. This dramatically increases concurrency without needing more threads, making it highly efficient for I/O-bound microservices.

- Uvicorn workers: FastAPI applications are typically run with an ASGI server like Uvicorn. The number of Uvicorn workers per instance is tuned based on CPU cores. For I/O-bound applications like an API Gateway that primarily publishes to Kafka, a higher number of workers than CPU cores can sometimes be beneficial to maximize concurrency during waiting periods.

- Non-blocking I/O: The underlying libraries used for interacting with Kafka producers (e.g., aiokafka or confluent-kafka-python in async mode) are designed to be non-blocking, ensuring that the API server remains responsive.

Achieving 20,000+ requests per minute (approx. 333 RPS) at the API Gateway requires a robust scaling strategy:

- Horizontal Scaling: Multiple instances of the FastAPI application are deployed, typically within a container orchestration platform like Kubernetes.

- Load Balancing (Nginx): An Nginx instance (or cloud-native load balancer) distributes incoming traffic across the FastAPI instances. Nginx is highly optimized for performance and can handle a vast number of concurrent connections with minimal overhead.

- Connection Pooling: Efficient management of connections to upstream services (like Kafka) prevents connection storming and reduces overhead.

- Idempotency: A critical feature in payment systems. Each payment request includes a unique idempotency_key. If the same request is received multiple times (e.g., due to network retries), the API Gateway ensures that only the first successful processing attempt results in a new event being published to Kafka. Subsequent identical requests with the same key would return the previous response without re-processing.

- Request Validation: Pydantic models are used to define strict schemas for incoming JSON payloads, automatically validating data types, formats, and required fields. Invalid requests are rejected early, reducing load on downstream services.

- Back-pressure: While Kafka itself handles back-pressure effectively by slowing down producers if brokers are overwhelmed, the API Gateway can implement its own back-pressure mechanisms through rate limiting (e.g., per IP, per merchant) or by returning 503 Service Unavailable if internal queues are full or Kafka is unresponsive. This prevents the system from being overwhelmed.

Nginx is deployed in front of the FastAPI cluster to act as a reverse proxy and load balancer.

- Features: TCP/HTTP load balancing, SSL termination, request routing, and caching.

- Algorithms: Round-robin, least connections, IP hash, etc., can be configured to distribute traffic optimally among the FastAPI instances.

- Health Checks: Nginx continuously monitors the health of upstream FastAPI servers, automatically removing unhealthy instances from the rotation.

FraudShield deliberately opts for asynchronous ingestion.

- Synchronous Ingestion: In a synchronous model, the API Gateway would wait for the entire fraud detection process (Kafka write, rule evaluation, database update) to complete before responding to the client. While providing immediate feedback on the final decision, this introduces significant latency and makes the API Gateway vulnerable to downstream slowdowns, drastically limiting throughput.

- Asynchronous Ingestion: FraudShield’s API Gateway immediately publishes the event to Kafka and returns an ACK or 202 Accepted response. The client is notified that the request has been received and is being processed, without waiting for the fraud decision. The actual fraud decision can then be communicated via webhooks, polling, or a separate query API. This decouples the ingestion from processing, allowing the API Gateway to achieve extremely high throughput and low latency. This is the preferred pattern for high-velocity, real-time systems where immediate final decision feedback isn’t strictly necessary for the initial API call.

4.2 Message Broker (Kafka)

Apache Kafka is the undisputed backbone of FraudShield’s real-time streaming architecture. Its capabilities are central to achieving the target throughput and ensuring data durability and scalability.

- High Throughput: Kafka is designed to handle millions of messages per second, making it ideal for the high-velocity payment data stream.

- Durability: Messages are persisted to disk and replicated across multiple brokers, ensuring no data loss even in the event of broker failures.

- Fault Tolerance: With proper replication and ISR (In-Sync Replicas) configuration, Kafka clusters can withstand broker failures without data loss or service interruption.

- Scalability: By adding more brokers and partitions, Kafka can scale horizontally to accommodate increasing data volumes and consumer loads.

- Decoupling: Producers and consumers are completely decoupled, allowing them to operate and scale independently.

The choice of partitioning strategy is crucial for parallelism and ordering guarantees:

- Key-based Partitioning: Kafka distributes messages to partitions based on a message key (e.g., payment_id, user_id, merchant_id). All messages with the same key are guaranteed to land on the same partition and thus be processed in order by a single consumer instance within a consumer group.

- payment_id: This ensures that all events related to a specific payment (e.g., initiation, update, refund) are processed in order.

- user_id / merchant_id: This is often preferred for fraud detection, as it allows velocity checks and behavioral analysis to be consistently applied to all transactions from a single user or merchant by a dedicated consumer.

- Hash-based Partitioning: If no specific ordering is required across a key, or if the key space is too small to distribute load evenly, a simple hash of the payment_id or another unique identifier can be used to spread messages evenly across partitions.

- FraudShield’s Approach: For FraudShield, a hash-based partitioning on a combination of user_id and merchant_id might be optimal. This ensures that a single consumer instance handles all transactions for a given user-merchant pair, simplifying stateful rule evaluation (e.g., velocity checks). If order is paramount for a single transaction lifecycle, then payment_id as the key for its specific topic.

- Ordering within a Partition: Kafka guarantees message order within a single partition. If global ordering across all messages is required, you’d need a single partition, which severely limits throughput.

- FraudShield’s Balance: By partitioning based on user_id or merchant_id, FraudShield achieves ordering guarantees relevant to fraud detection (e.g., all transactions for a specific user are processed chronologically) while still distributing load across multiple partitions and consumers to maintain high throughput. This is a common and effective compromise.

Optimizing Kafka producers is vital for performance:

- Batching: Producers can buffer multiple messages and send them as a single batch to Kafka. This significantly reduces network overhead and improves throughput. (batch.size, linger.ms configuration).

- Compression: Messages can be compressed (e.g., Gzip, Snappy, LZ4) before sending to Kafka, reducing network bandwidth usage and storage requirements on brokers, at the cost of a slight increase in CPU usage on the producer and consumer.

- acks Configuration: Controls the durability guarantee of a produced message.

- acks=0: Producer doesn’t wait for acknowledgment. Highest throughput, lowest durability (messages might be lost).

- acks=1: Producer waits for the leader replica to acknowledge the write. Good balance of throughput and durability.

- acks=all (or -1): Producer waits for all in-sync replicas to acknowledge the write. Lowest throughput, highest durability (guarantees no data loss).

- FraudShield’s Choice: For payment requests, acks=all is highly recommended to ensure no payment events are lost. The ingestion layer’s primary role is to get the event safely into Kafka.

- Replication Factor: For each topic, the replication factor defines how many copies of each partition are maintained across different brokers. A factor of 3 (one leader, two followers) is standard for production, allowing for two broker failures without data loss.

- In-Sync Replicas (ISR): Kafka tracks which replicas are fully caught up with the leader. Only replicas in the ISR set are considered for failover. If a leader fails, a new leader is elected from the ISR.

- min.insync.replicas: This producer and broker configuration ensures that a message is only considered committed if it has been written to at least this many in-sync replicas. Combined with acks=all, this provides strong durability guarantees.

While other message brokers exist, Kafka is typically the superior choice for high-throughput, real-time streaming in fraud detection:

- RabbitMQ: Excellent for traditional message queuing (work queues, pub/sub), but less performant for persistent, high-volume stream processing and lacks Kafka’s built-in replication for stream durability.

- Apache Pulsar: A strong competitor with similar features to Kafka (segment-based storage, geo-replication), and often cited for its more flexible consumer model. However, Kafka has a larger ecosystem, more mature tooling, and broader community adoption, making it a safer bet for critical systems unless Pulsar’s specific features (e.g., tiered storage) are a primary driver.

- Redis Streams: A good choice for simple, low-latency stream processing within the Redis ecosystem, but not designed for the same scale, durability, and fault tolerance as Kafka for a system-wide backbone. More suitable for localized, high-speed data exchange between microservices using Redis.

- Why Kafka Wins for FraudShield: Its unparalleled performance for high-volume streaming, robust fault tolerance, mature ecosystem, and strong guarantees around message durability and ordering (within partitions) make it the ideal central nervous system for FraudShield.

4.3 Fraud Detection Consumer & Rule Engine

This is the intellectual core of FraudShield, where the actual fraud detection logic resides. Multiple instances of this service consume events from Kafka and apply rules in real-time.

- Stateless by Design (with Managed State): While individual rule evaluations can be stateless, effective fraud detection often requires stateful checks (e.g., “has this user made more than 5 transactions in the last hour?”). The consumer itself tries to remain stateless in its processing logic but intelligently leverages an external, shared state store (Redis) for fast lookups.

- High Parallelism: Designed to scale horizontally by adding more consumer instances, each processing messages from different Kafka partitions.

- Fault Tolerant: Leverages Kafka’s consumer group rebalancing and offset management to ensure that if a consumer fails, another can take over its partitions seamlessly without losing messages.

- Optimized for Performance: Focus on minimizing I/O and CPU cycles during rule evaluation.

- aiokafka (Python): This library provides an asynchronous Kafka client, perfectly aligning with Python’s asyncio paradigm. It allows a single consumer instance to handle multiple messages concurrently (within the same thread) while waiting for I/O operations (like Redis lookups or Kafka acknowledgments), significantly improving resource utilization.

- confluent-kafka-python: A wrapper around librdkafka, a high-performance C library. It also supports asynchronous message delivery and processing and is often chosen for maximum throughput and reliability in Python.

- FraudShield’s Choice: aiokafka would likely be used to leverage the async/await pattern throughout the Fraud Detection Service, maintaining a consistent asynchronous programming model.

- Stateless Rules: Rules that can be evaluated purely based on the current transaction’s data (e.g., “transaction amount > $10,000,” “country of origin is blacklisted”). These are fast and easy to implement.

- Stateful Rules: Rules that require historical context or aggregated data over a period (e.g., “user made 5 transactions in 10 minutes,” “merchant has an unusually high refund rate”). These necessitate access to a state store.

- FraudShield’s Hybrid Approach: The rule engine combines both. Stateless rules are evaluated first for quick rejections. Stateful rules rely on Redis for sub-millisecond access to aggregated data, effectively making them “pseudo-stateless” from the consumer’s perspective, as the state is externalized and quickly accessible.

- Consume Message: An aiokafka consumer instance fetches a batch of messages from its assigned Kafka partitions.

- Deserialize: The JSON message payload is deserialized into a Python object (e.g., Pydantic model for validation).

- Pre-processing/Enrichment: Basic data cleaning or real-time enrichment might occur (e.g., normalizing currency, quickly looking up internal static data).

- Rule Evaluation Loop:

- Rule Prioritization: Rules are typically prioritized (e.g., simple, fast rules first).

- Redis Lookups: For stateful rules, efficient Redis queries retrieve necessary historical data (e.g., incrementing velocity counters, checking blacklists).

- Rule Logic Execution: Each rule is executed. Rules can be chained or weighted.

- Decision: Based on rule outcomes, a fraud score or decision (approve, decline, review) is generated.

- Post-processing/Action:

- Publish Decision: The fraud decision and enriched transaction details are published to another Kafka topic (e.g., fraud-decisions) for downstream systems (e.g., authorization service, data warehouse).

- Update State (Redis): If a rule updated state (e.g., incremented a velocity counter), that updated state is asynchronously written back to Redis.

- Commit Offset: The consumer commits its offset to Kafka, acknowledging successful processing of the message.

- Consumer Batching: Kafka consumers fetch messages in batches. The max.poll.records and fetch.min.bytesconfigurations control this. Processing messages in batches reduces the overhead of individual message processing.

- Pre-fetching: While the consumer processes one batch, it can pre-fetch the next batch in the background, minimizing idle time.

- Processing Concurrency: Within a single consumer instance, asyncio allows for concurrent execution of I/O-bound tasks. For CPU-bound rules, multiple consumer instances (each in its own thread or process) across different Kafka partitions provide true parallelism.

Redis is indispensable here. It acts as an extremely fast key-value store for:

- Velocity Checks: Tracking transaction counts, sums, or unique card numbers for a user/merchant within specific time windows (e.g., 5 transactions in 1 hour).

- Blacklists/Whitelists: Storing known fraudulent accounts, IP addresses, or safe entities for instant rejection/approval.

- Merchant-Specific Thresholds: Storing dynamic risk thresholds or rules for individual merchants.

- Counters: Maintaining counts of specific events (e.g., failed login attempts, chargebacks) for a user.

Kafka’s consumer group mechanism inherently supports scaling.

- Consumer Group: All instances of the Fraud Detection Service form a single consumer group.

- Partition Assignment: Kafka ensures that each partition is consumed by exactly one consumer instance within a group at any given time.

- Horizontal Scaling: To increase throughput, more instances of the Fraud Detection Service are added to the consumer group. Kafka automatically rebalances partitions among the available instances. If there are 10 partitions and 5 consumer instances, each instance will consume from 2 partitions. If 5 more instances are added, each will consume from 1 partition, effectively doubling processing capacity (up to the number of partitions).

- I/O-bound Rules: Rules involving Redis lookups or external API calls. These benefit significantly from asyncio and non-blocking I/O, allowing other tasks to proceed while waiting for I/O.

- CPU-bound Rules: Rules involving complex calculations, regex matching, or data transformations. These benefit from true parallelism, meaning deploying more CPU cores and more consumer instances (which implies more Kafka partitions to distribute the load). Python’s GIL means that for heavy CPU tasks, multiple processes are needed, not just multiple threads within one process. Therefore, ensure that Uvicorn workers (if used for multiple threads) or Kubernetes pods provide adequate CPU resources and that Kafka partitions are sufficient to distribute this CPU load.

4.4 Data Storage Layer (PostgreSQL)

PostgreSQL serves as the robust and reliable primary data store for FraudShield, handling both transactional data and providing a foundation for analytics.

- Transactional Tables: Optimized for fast writes and point lookups for current transactions.

- transactions table: id (PK), payment_id, user_id, merchant_id, amount, currency, timestamp, status, fraud_score, fraud_decision, metadata_jsonb.

- users, merchants, payment_methods tables: Supporting master data.

- Analytical Separation (De-normalized for reporting): While not fully separate data warehouses, views or materialized views can be created for reporting. For truly large-scale analytics, data would be exported to a dedicated data warehouse (e.g., via Kafka Connect to Snowflake, Redshift, or a data lake).

- JSONB Column: Using jsonb columns in PostgreSQL for metadata allows flexible storage of semi-structured data from payment requests without frequent schema migrations, which is common in fraud detection where new features or data points are constantly added.

To handle 28M+ transactions/day (approx. 333 writes/sec), write optimization is critical:

- Batch Inserts: Instead of inserting each transaction individually, FraudShield’s database consumer batches multiple fraud decisions/transaction records and inserts them using a single INSERT statement (e.g., INSERT INTO transactions VALUES (…), (…), …;). This dramatically reduces the number of round trips to the database and I/O overhead.

- Asynchronous Writes: The database consumer can acknowledge messages to Kafka immediately after receiving them, and then perform the batch writes to PostgreSQL asynchronously. This further decouples the DB write from Kafka consumption logic.

- Partitioned Tables: For very large tables (e.g., transactions), PostgreSQL’s native table partitioning (by timestamp or user_id range) can improve query performance and simplify data retention policies. Queries often touch only a subset of partitions, and old partitions can be detached/archived easily.

- Indexing: Proper indexing is paramount for query performance.

- Primary keys (id) and foreign keys (user_id, merchant_id).

- Frequently queried columns: timestamp (for time-series queries), status, fraud_decision.

- Partial indexes: For specific high-cardinality conditions (e.g., CREATE INDEX ON transactions (user_id) WHERE fraud_decision = ‘decline’;).

- GIN indexes for jsonb columns if specific keys within metadata_jsonb are frequently queried.

- Storage: SSDs are essential for high I/O throughput.

- Retention Policies: Implement strategies to archive or purge old data to manage database size and maintain performance.

- Problem: Each application connection to PostgreSQL consumes resources on the database server. High-concurrency applications can overwhelm the database with too many connections.

- Solution: PgBouncer is a lightweight connection pooler. It sits between the application and PostgreSQL, maintaining a pool of persistent connections to the database. Application connections connect to PgBouncer, which then efficiently reuses its own connections to the database. This significantly reduces database overhead, improves performance, and increases the number of concurrent application connections that can be supported.

- To offload read-heavy analytical queries and dashboard reporting, PostgreSQL read replicas are employed. These are asynchronous copies of the primary database.

- Benefits: Reduces load on the primary (write-master) database, ensures that analytical queries do not impact the performance of real-time transaction processing.

- FraudShield Use Case: BI tools, anti-fraud analyst dashboards, and historical data queries would connect to the read replicas.

- Apache Cassandra: A highly scalable, distributed NoSQL database excellent for write-heavy, eventually consistent workloads. While suitable for storing high volumes of transaction data, its eventual consistency model and less mature support for complex analytical queries (compared to PostgreSQL) made it less ideal as the primary source of truth for all transactional data where ACID properties are often desired.

- ClickHouse: An analytical columnar database, incredibly fast for OLAP queries on massive datasets. Excellent for fraud analytics and reporting, but not designed for transactional, row-level updates or point lookups that a system like FraudShield requires as its primary store. It could be a strong candidate for an analytics-specific data warehouse for FraudShield.

- TimescaleDB: An extension to PostgreSQL that turns it into a powerful time-series database. It offers excellent performance for time-series data (like transaction events) with SQL queries. It was a strong contender, but standard PostgreSQL with proper partitioning and indexing can often suffice, especially if the primary use case is not exclusively time-series analytics.

- Why PostgreSQL Wins: For FraudShield’s core requirement of reliable transactional storage, robust indexing for diverse queries, strong consistency, and a mature ecosystem, PostgreSQL strikes the best balance. Its extensibility (e.g., jsonb, PostGIS) also offers future flexibility.

4.5 Caching Layer (Redis)

Redis is an indispensable component in FraudShield, serving as a high-speed, in-memory cache that significantly reduces latency for critical fraud detection lookups.

Fraud detection often involves frequent checks against dynamic data that changes quickly or static data that must be retrieved instantly. Hitting the main database for every such lookup would introduce unacceptable latency. Redis provides sub-millisecond access to this “hot data,” enabling real-time rule evaluation without bogging down the primary database.

- Merchant Thresholds: Storing specific risk thresholds or rule configurations for individual merchants. Instead of fetching from DB, Redis provides instant access.

- Example: merchant:{id}:max_tx_amount, merchant:{id}:allowed_countries.

- Velocity Checks: Tracking the frequency or aggregate amount of transactions over a rolling time window.

- Example: user:{id}:tx_count:last_hour, card:{number}:tx_sum:last_24h. Redis’s atomic increment/decrement operations and sorted sets (for time-windowed data) are perfect here.

- Blacklists/Whitelists: Storing lists of known fraudulent IP addresses, email domains, card numbers, or trusted entities.

- Example: blacklist:ip:{ip_address}, whitelist:user:{id}. Redis sets provide O(1) lookups.

- Session Data: Temporary storage for ongoing fraud investigation sessions.

- Temporary Counters: For specific, short-lived event counts during processing.

- Time-To-Live (TTL): Most cached data in Redis will have a defined TTL.

- Velocity checks: TTL corresponds to the window (e.g., 1 hour, 24 hours).

- Blacklists: Can be longer, but still have a TTL to ensure eventual consistency with the source of truth (e.g., a database that stores the definitive blacklist).

- Write-Through / Write-Aside: When the authoritative source of truth (e.g., PostgreSQL for blacklists, or the Fraud Detection Service for velocity updates) changes, the cache should be updated.

- Write-through: Updates Redis synchronously with the primary store.

- Write-aside: Updates the primary store, then separately updates or invalidates Redis. FraudShield likely uses a mix, with the Fraud Detection Service writing velocity updates directly to Redis after processing.

- Pub/Sub for Invalidation: For critical, globally shared data like blacklists, a change in the primary database might trigger a Kafka message that instructs all Fraud Detection Service instances (via a dedicated Kafka topic) to invalidate or refresh specific Redis keys.

- Redis Cluster: For high availability and horizontal scaling, Redis Cluster is the go-to solution. It partitions data across multiple Redis nodes (shards), each with its own master and replica(s).

- Sharding: Data is automatically sharded based on key hashes, distributing the load across the cluster. This allows for significantly more memory and higher throughput than a single Redis instance.

- High Availability: Each master node in a shard can have one or more replicas. If a master fails, one of its replicas is automatically promoted to master, ensuring continuous operation.

- FraudShield’s Setup: A multi-node Redis Cluster with a replication factor of at least 1 (one master, one replica per shard) would be deployed to guarantee uptime and handle the read/write load from multiple Fraud Detection Service instances.

4.6 Monitoring and Observability

A production-grade system handling sensitive financial data at high velocity demands comprehensive monitoring and observability. Without it, debugging, performance optimization, and proactive issue detection would be impossible.

- Prometheus: A powerful open-source monitoring system that collects and stores time-series data. It pulls metrics from instrumented applications and infrastructure.

- Grafana: An open-source analytics and visualization platform that allows creating dashboards from various data sources, including Prometheus.

- Key Metrics Monitored:

- Kafka: Consumer group lag (crucial for detecting processing bottlenecks), broker health, topic throughput (messages/sec, bytes/sec), partition state.

- FastAPI Gateway: Request per second (RPS), P99/P95/P50 latency, error rates (HTTP 4xx/5xx), CPU/memory usage of instances.

- Fraud Detection Service: Messages processed/sec, rule evaluation latency, Redis lookup latency, CPU/memory usage, number of fraud decisions (approve/decline/review).

- PostgreSQL: Query latency, connection count, CPU/memory/disk I/O, replication lag.

- Redis: Cache hit ratio, command latency, memory usage, network I/O.

- Dashboards: Dedicated Grafana dashboards for each service and for end-to-end flow, providing a real-time operational view.

- ELK Stack (Elasticsearch, Logstash, Kibana):

- Logstash: Collects logs from all services.

- Elasticsearch: Stores and indexes logs for fast searching.

- Kibana: Provides a web interface for searching, analyzing, and visualizing logs.

- Purpose: Centralized logging simplifies troubleshooting by allowing developers to search across all service logs for error messages, stack traces, and contextual information.

- OpenTelemetry (Distributed Tracing):

- Problem: In a microservice architecture, a single request traverses multiple services. Debugging latency or errors across these boundaries is challenging.

- Solution: OpenTelemetry provides a standardized way to instrument services to generate traces. Each request is assigned a trace_id that is propagated across service calls. Spans within a trace represent individual operations (e.g., API call, Kafka publish, Redis lookup).

- Benefits: Visualizes the entire request flow, identifies latency bottlenecks in specific services, and pinpoints exactly which service failed within a distributed transaction. Traces are typically sent to a backend like Jaeger, Zipkin, or commercial APM tools.

- Grafana dashboards are configured to explicitly display key metrics related to SLAs, such as:

- P99 latency of fraud decisioning: A critical metric to ensure the 500ms target is met.

- Throughput (RPS): Ensuring the system consistently processes 20,000+ requests/min.

- Error Rates: Monitoring for any spikes in application or system errors.

- Kafka Consumer Lag: Directly indicating if the fraud detection service is keeping up with incoming events.

- Thresholds are set on these metrics, triggering alerts if SLA targets are approached or breached.

- Alerting: Prometheus Alertmanager integrates with Grafana to send notifications (Slack, PagerDuty, email) when predefined thresholds are crossed (e.g., high latency, high error rate, Kafka lag).

- Autoscaling:

- Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA): Can scale service replicas (pods) based on CPU utilization or custom metrics (e.g., Kafka consumer lag via KEDA).

- KEDA (Kubernetes Event-Driven Autoscaling): A powerful tool that allows Kubernetes to scale any container based on event sources (like Kafka queue depth, Redis streams length, Prometheus metrics).

- FraudShield’s Use: KEDA would be configured to monitor Kafka consumer lag for the Fraud Detection Service. If lag increases (indicating messages are building up), KEDA automatically scales up the number of Fraud Detection Service pods to increase processing capacity. When lag subsides, it scales them down, optimizing resource utilization.

- Custom Scaling Policies: Can be implemented for more complex scenarios, but KEDA provides a robust and declarative approach for event-driven scaling.

5. Low-Level Design (LLD)

The high-level architecture defines what services exist; the low-level design specifies how these services are built and interact at a granular level. This section details the internal structure and communication contracts within FraudShield.

5.1 Class and module interactions in FraudShield

A well-structured codebase is crucial for maintainability, extensibility, and testability. For Python-based microservices like the Fraud Detection Service and API Gateway, a typical structure would involve:

Example Fraud Detection Service Module Structure

fraudshield/

├── .gitignore

├── LICENSE

├── README.md

├── alembic.ini

├── docker-compose.yml

├── requirements.txt

├── Designing FraudShield: A Scalable, Real-Time Fraud Detection System for 20,000+ Payment Requests per Minute – Kuldeepstechwork.pdf

├── migrations/

├── src/

│ ├── init.py

│ ├── common/

│ │ ├── init.py

│ │ ├── config.py

│ │ ├── db.py

│ │ ├── kafka_utils.py

│ │ └── redis_utils.py

│ ├── models/

│ │ ├── init.py

│ │ ├── base.py

│ │ ├── payment_models.py

│ │ ├── user_models.py

│ │ └── fraud_models.py

│ ├── services/

│ │ ├── detector/

│ │ │ ├── init.py

│ │ │ ├── app.py

│ │ │ ├── main.py

│ │ │ ├── db.py

│ │ │ ├── dependencies.py

│ │ │ ├── crud.py

│ │ │ ├── models.py

│ │ │ ├── api/

│ │ │ │ ├── init.py

│ │ │ │ ├── endpoints_v1.py

│ │ │ │ └── health.py

│ │ │ └── schemas/

│ │ │ ├── init.py

│ │ │ ├── payment.py

│ │ │ ├── user.py

│ │ │ ├── merchant.py

│ │ │ ├── alert.py

│ │ │ └── fraud.py

│ │ ├── fraud_consumer/

│ │ │ ├── init.py

│ │ │ ├── main.py

│ │ │ ├── consumer_logic.py

│ │ │ ├── rule_engine.py

│ │ │ ├── models.py

│ │ │ └── rules/

│ │ │ ├── base_rule.py

│ │ │ ├── blacklist_rule.py

│ │ │ └── velocity_rule.py

│ │ ├── producer_cli/

│ │ │ ├── init.py

│ │ │ ├── send_payment.py

│ │ │ └── load_test.py

│ │ └── decision_persistor/

│ │ └── main.py

└── test/

Key Interactions:

- Client -> Ingest API: POST /api/v1/payments/ — client sends a payment event (synchronous validation); API responds

202 Acceptedwith a payment_id. The service immediately publishes the canonical message to Kafka topicraw_paymentsand returns to the client so heavy processing happens asynchronously. - Detector -> Kafka: The detector produces messages to

raw_paymentsusing a stable message key composed from configured fields (default country|payment_method). This ensures per-key ordering and partition affinity. - Worker -> Consume & Enrich: The fraud consumer group subscribes to

raw_payments, processes each message, computes fraud score and rules triggered, writes authoritative records to Postgres (payments, alerts), and publishes enriched messages toprocessed_paymentsand alerts tofraud_alerts. Offsets are committed only after successful processing and downstream publish. - Client -> Query status: GET /api/v1/payments/{payment_id} — client polls to fetch persisted result, fraud score, and reason codes.

- Observability & Ops: Monitor consumer group lag, topic partitions, queue depth and processing latency. DLQ topic recommended for failed messages after retry.

For Code: Classes and modules

Kindly check code here https://github.com/kuldeepstechwork/fraudshield .

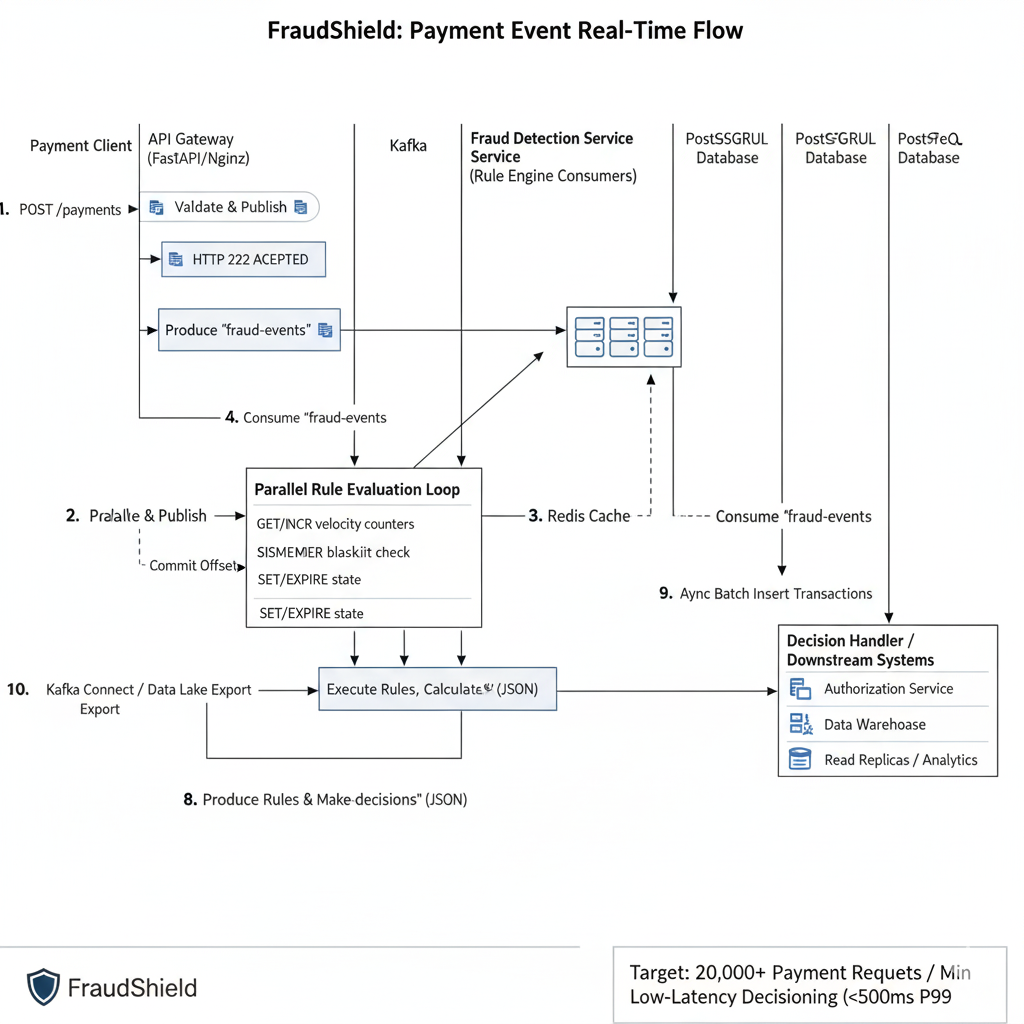

5.2 Example sequence diagram: Payment → Kafka → Rule Engine → DB → Enrichment topic

Detailed Steps in the Sequence Diagram:

- Payment Client -> API Gateway: A Payment Client sends a POST /payments request (containing PaymentRequest JSON) to the API Gateway.

- API Gateway Processing:

- The API Gateway (FastAPI instance) validates the incoming PaymentRequest against its Pydantic schema.

- It publishes the validated PaymentRequest as a message to the fraud-events Kafka topic.

- It immediately returns an HTTP 202 ACCEPTED response to the Payment Client, acknowledging receipt.

- Kafka Broker: The fraud-events message is queued in Kafka, awaiting consumption.

- Fraud Detection Service (FDS) Consumption: Multiple instances of the Fraud Detection Service (Rule Engine Consumers) are part of a Kafka consumer group. One instance consumes the fraud-events message from its assigned partition.

- FDS Rule Evaluation Loop:

- The FDS service initiates a Parallel Rule Evaluation Loop.

- For stateful rules (e.g., velocity checks, blacklist lookups), it interacts with Redis Cache:

- GET/INCR for velocity counters.

- SISMEMBER for blacklist checks.

- SET/EXPIRE to update state (e.g., set TTLs for counters).

- It executes various Rules and calculates a Fraud Score and Decision.

- FDS Produces Decision: The FDS service produces the FraudDecisionEvent (including transaction_id, decision, fraud_score, rules_triggered, etc.) to the fraud-decisions Kafka topic.

- FDS Commits Offset: After successfully processing and producing the decision, the FDS consumer commits its offset for the fraud-events topic to Kafka.

- Database Consumer: A separate consumer (or the FDS itself, often decoupled) consumes fraud-decisions events.

- Async Batch Insert to PostgreSQL: This consumer performs Async Batch Inserts of the transaction and fraud decision data into the PostgreSQL Database. This is a more efficient write pattern for high volume.

- Decision Handler / Downstream Systems: Other downstream systems or services also consume from the fraud-decisionstopic:

- Authorization Service: Receives the decision to approve or decline the original payment.

- Data Warehouse / BI Tools: For historical analysis and reporting.

- Read Replicas / Analytics: Can query the PostgreSQL database for analytics without impacting the primary DB.

- Kafka Connect / Data Lake Export: Potentially, Kafka Connectors can automatically export data from Kafka topics to a Data Lake (e.g., S3) or other analytical stores for further processing.

5.3 Fault tolerance patterns (retry queues, DLQ, idempotency keys)

FraudShield integrates several fault tolerance patterns to ensure reliability in a distributed environment:

- Idempotency Keys: As discussed in 4.1, the idempotency_key (sent by the client) is critical. The API Gateway ensures that even if a client retries a request multiple times due to network issues, only the first successfully processed request (that publishes to Kafka) results in a new action. Subsequent identical requests yield the same result.

- Retry Mechanisms (Kafka Consumers):

- Automatic Retries: Kafka consumers are designed to retry processing messages if an error occurs. If an unhandled exception or transient error occurs during rule evaluation, the consumer will typically retry the message.

- Exponential Backoff: If errors persist, consumers can implement exponential backoff before retrying to avoid overwhelming the failing downstream service.

- Retry Topics: For more controlled retries, messages that fail processing can be sent to a dedicated “retry topic” with a delay. A separate consumer then picks up these messages after a set interval. This prevents a single problematic message from blocking an entire partition.

- Dead-Letter Queue (DLQ):

- Messages that repeatedly fail processing after a configured number of retries (e.g., due to unrecoverable data errors or persistent logic bugs) are moved to a Dead-Letter Queue (DLQ) topic (e.g., fraud-events-dlq).

- Purpose: The DLQ prevents poisoned messages from indefinitely blocking the main processing pipeline. It acts as a holding area for problematic messages that can be manually inspected, debugged, fixed, and potentially re-processed later, minimizing impact on real-time operations.

- Consumer Group Rebalancing: Kafka’s consumer groups automatically handle failures. If a consumer instance crashes, Kafka detects it and reassigns its partitions to other healthy consumers in the group, ensuring continuous processing.

- acks=all (Kafka Producers): As detailed in 4.2, producers configured with acks=all ensure that messages are durably written to all in-sync replicas before acknowledging success, preventing data loss at the source.

- Circuit Breakers (Optional, for External Calls): If the Fraud Detection Service makes synchronous calls to external third-party services for enrichment, a circuit breaker pattern (e.g., using tenacity library in Python) can prevent cascading failures. If an external service is consistently failing, the circuit breaker “trips,” preventing further calls for a period, gracefully failing fast, and allowing the external service to recover.

6. Scaling Strategy for 20,000 Requests per Minute

Achieving the target throughput of 20,000 payment requests per minute (approximately 333 RPS) requires a methodical approach to scaling each component, identifying potential bottlenecks, and applying appropriate horizontal scaling techniques.

6.1 Throughput calculation breakdown (RPS, CPU, DB writes)

Let’s break down the implications of 333 RPS:

- API Gateway: Needs to handle 333 HTTP POST requests per second. Since it’s primarily I/O-bound (validating and publishing to Kafka), FastAPI instances can achieve high concurrency per core.

- Kafka: Needs to handle 333 messages/sec for fraud-events topic and 333 messages/sec for fraud-decisions topic, plus internal broker traffic.

- Fraud Detection Service (Consumers): Needs to process 333 messages/sec, which involves:

- Deserialization

- Multiple Redis lookups (e.g., 2-5 per transaction)

- Rule evaluation logic (CPU-bound)

- Publishing to fraud-decisions topic

- PostgreSQL Database: Needs to handle 333 transactions/sec of write operations (inserts). With batching, this translates to fewer, larger write operations (e.g., 33 batches of 10 messages every second, or 10 batches of 33 messages). Read replicas handle analytical queries.

- Redis: Needs to handle 333 * (number of Redis lookups per transaction) read/write operations per second. If 3 lookups per transaction, that’s ~1000 Redis ops/sec.

6.2 Horizontal scaling of API layer

- Strategy: Deploy multiple FastAPI application instances behind a load balancer (Nginx or cloud-native ALB/NLB).

- Implementation: Using Kubernetes, define a Deployment for the FastAPI service and expose it via a Service and Ingress.

- Autoscaling: Configure a Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) based on CPU utilization. If average CPU across FastAPI pods exceeds (e.g.) 60%, new pods are spun up. A more sophisticated HPA could also use RPS metrics from Prometheus.

- Example: With FastAPI being efficient, a few instances (e.g., 3-5 pods, each with 2-4 CPU cores) should easily handle 333 RPS, as its primary task is fast I/O to Kafka.

6.3 Kafka partitioning and consumer group scaling

- Partitions: The number of Kafka partitions for fraud-events is crucial. It directly dictates the maximum parallelism for the Fraud Detection Service consumers. If there are N partitions, there can be at most N active consumer instances in the consumer group simultaneously processing messages.

- Recommendation: Start with a healthy number, e.g., 10-20 partitions for fraud-events. This allows for sufficient scaling headroom. The fraud-decisions topic might need fewer, as it’s an output, but a similar logic applies.

- Consumer Group Scaling:

- KEDA (Kubernetes Event-Driven Autoscaling): This is the ideal tool. Configure KEDA to monitor the lag metric of the fraud-events consumer group.

- Policy: If the Kafka consumer lag (number of unread messages) for the Fraud Detection Service consumer group goes above a certain threshold (e.g., 1000 messages), KEDA will automatically scale up the number of Fraud Detection Service pods.

- Scale Down: When lag reduces, KEDA scales down the pods to optimize resource usage.

- Result: This ensures that the Fraud Detection Service can dynamically adjust its processing capacity to match the incoming event rate, preventing backlogs.

6.4 Database bottleneck mitigation (batching, async writes)

The PostgreSQL database is often the trickiest component to scale due to its stateful nature and ACID requirements.

- Batch Inserts: As covered in 4.4, the database consumer performing batch inserts dramatically reduces the write load on the primary database by amortizing the cost of transactions and disk writes.

- Connection Pooling (PgBouncer): Essential to reduce the overhead of managing connections for the database consumer, especially if multiple database consumer instances are running.

- Read Replicas: Critical for offloading all analytical and dashboard queries from the primary write master.

- Vertical Scaling (Initial): Initially, ensure the PostgreSQL instance is provisioned with sufficient CPU, RAM, and fast SSD storage.

- Sharding (Future): If 20,000 RPS becomes much higher (e.g., 100,000+ RPS), database sharding (e.g., by merchant_id or user_id range) might be considered, but it adds significant operational complexity. PostgreSQL partitioning helps defer this.

6.5 Autoscaling policies with KEDA and Kubernetes HPA

- Type: Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA).

- Metric: Average CPU utilization across pods.

- Threshold: e.g., targetAverageUtilization: 60%.

- Min/Max Replicas: e.g., minReplicas: 3, maxReplicas: 10.

- Type: KEDA ScaledObject.

- Metric: Kafka consumer group lag for fraud-events topic.

- Threshold: e.g., lagThreshold: 1000, messageLatency: 500ms.

- Min/Max Replicas: e.g., minReplicas: 5, maxReplicas: 20 (depending on Kafka partitions and rule complexity).

- Type: KEDA ScaledObject (monitoring fraud-decisions topic lag) or HPA on CPU.

6.6 Load testing results (locust, k6, or wrk reports)

Before going to production, extensive load testing is critical to validate the scaling strategy and identify bottlenecks.

- Tools:

- Locust: Python-based, easy to write scripts for complex user flows.

- k6: JavaScript-based, excellent for API and protocol-level testing, good for measuring response times and throughput.

- wrk: Command-line HTTP benchmarking tool, very fast for raw HTTP performance testing.

- Methodology:

- Simulate 333 RPS (and gradually increase to test limits).

- Measure end-to-end latency (from client request to fraud decision event in fraud-decisions topic).

- Monitor CPU, memory, network I/O, Kafka lag, Redis latency, and database metrics.

- Expected Report: A summary showing that FraudShield can consistently achieve P99 latency < 500ms at 333 RPS with specific resource utilization levels, validating the architectural choices. This report would highlight areas of optimization if the targets are not met.

7. Performance Optimization and Bottleneck Analysis

Even with a scalable design, continuous performance optimization and bottleneck analysis are essential to maintain efficiency and meet demanding SLAs.

7.1 Identifying system hot paths

- Definition: Hot paths are the code segments or system flows that are executed most frequently or consume the most resources, directly impacting latency and throughput.

- Examples in FraudShield:

- Deserialization of Kafka messages in the Fraud Detection Service.

- Redis lookups for velocity checks.

- Complex rule evaluations within the Rule Engine.

- Database batch inserts.

- Tools: Distributed tracing (OpenTelemetry), CPU/memory profilers (Py-Spy, cProfile for Python), database query analyzers (EXPLAIN ANALYZE in PostgreSQL).

7.2 CPU, memory, and I/O profiling

- CPU Profiling:

- Purpose: Identify functions or code blocks consuming the most CPU cycles.

- Tools: Py-Spy for sampling, cProfile for deterministic profiling.

- Action: Optimize algorithms, reduce unnecessary computations, use more efficient data structures.

- Memory Profiling:

- Purpose: Detect memory leaks or excessive memory consumption, which can lead to OOM (Out Of Memory) errors or inefficient garbage collection.

- Tools: memory_profiler for Python.

- Action: Optimize data storage, release unused resources, avoid loading entire datasets into memory.

- I/O Profiling:

- Purpose: Identify bottlenecks related to disk reads/writes, network calls (Kafka, Redis, DB).

- Tools: iostat, netstat (system level), OpenTelemetry traces for service-level I/O.

- Action: Batch I/O operations, use non-blocking I/O, optimize network configurations, use faster storage (SSDs).

7.3 Reducing rule evaluation latency

- Rule Prioritization: Evaluate faster, simple rules first (e.g., blacklists, exact matches) and short-circuit evaluation if a definitive decision can be made.

- Optimized Redis Access: Ensure Redis queries are efficient (e.g., SISMEMBER for sets, HGETALL for hashes, INCR for counters). Batch Redis commands using pipeline where possible.

- Pre-computed Features: For complex features (e.g., “average transaction amount for user in last 3 days”), consider pre-computing them in a separate stream processing job (e.g., using Kafka Streams or a Flink job) and storing them in Redis, rather than calculating them on-demand during rule evaluation.

- Rule Set Optimization: Regularly review and optimize the rule set for redundancy or inefficiency.

7.4 Connection pooling and network optimization

- Connection Pooling (PgBouncer, Redis connection pools): Already discussed, but critical for minimizing overhead. Each microservice should use a connection pool for its database and Redis connections.

- Network Optimization:

- Reduce Network Hops: Keep related services in the same network or availability zone to minimize latency.

- Efficient Protocols: Utilize binary protocols (e.g., Kafka’s native protocol) where possible instead of less efficient text-based ones.

- Compression: Enable message compression in Kafka producers to reduce network bandwidth.

- MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) Tuning: Ensuring optimal MTU settings for network interfaces.

7.5 Async task scheduling and back-pressure control

- Asyncio (Python): Proper use of async/await patterns ensures that I/O-bound tasks don’t block the event loop, maximizing the concurrency of a single thread.

- Task Queues for Non-Critical Background Tasks: For any tasks that are not strictly real-time and can tolerate delay (e.g., certain types of logging, sending non-critical notifications), use a separate task queue (like Celery with Redis/RabbitMQ) to offload them from the main processing path.

- Back-pressure at Source: Implement rate limiting at the API Gateway to prevent downstream services from being overwhelmed if they start showing signs of strain (e.g., increasing Kafka lag, rising latency). Return 429 Too Many Requestsor 503 Service Unavailable proactively.

7.6 Trade-off between model accuracy and response latency

- Tiered Approach: A common strategy in fraud detection.

- Tier 1 (Low Latency, High Throughput): Fast, simple rules (e.g., blacklists, simple velocity checks) or lightweight ML models (e.g., logistic regression, decision trees) that can provide a quick “approve” or “decline” for the majority of transactions.

- Tier 2 (Higher Latency, More Accurate): Transactions that pass Tier 1 but are still suspicious are routed for more intensive analysis. This might involve calling more complex ML models (e.g., deep learning models), external data enrichment services, or human review. This analysis can happen asynchronously, where the initial decision is “review” and a final decision comes later.

- Feature Engineering for Speed: Design features for ML models that can be quickly computed or retrieved from cache. Avoid features that require expensive, synchronous database queries.

- Model Simplification/Quantization: For real-time ML inference, explore model optimization

7.6 Trade-off between model accuracy and response latency (Cont.)

- Model Simplification/Quantization: For real-time ML inference, explore model optimization techniques such as model quantization (reducing precision of weights) or pruning (removing less important connections) to make models smaller and faster, potentially at a minimal cost to accuracy.

- A/B Testing and Canary Deployments: Continuously test different rule sets or model versions in production (on a small percentage of traffic) to find the optimal balance between detection accuracy (reducing false positives and false negatives) and the latency implications.

8. Reliability, Fault Tolerance, and Recovery

For a system dealing with financial transactions, data integrity, continuous availability, and the ability to recover from failures are paramount. FraudShield incorporates robust reliability and fault tolerance patterns.

8.1 Ensuring exactly-once processing with Kafka + DB

Achieving “exactly-once” processing semantics in a distributed system is notoriously challenging. Kafka itself guarantees “at least once” message delivery, meaning a message might be delivered multiple times. To mitigate this for critical operations like database writes, FraudShield combines several strategies:

- Idempotent Consumers/Producers:

- Kafka Producers: Configuring Kafka producers for idempotent delivery (enable.idempotence=true) guarantees that retries on the producer side will not result in duplicate messages being written to Kafka, assuming a single producer instance per session.

- Application-Level Idempotency (Fraud Detection Service): When the Fraud Detection Service publishes its decision to fraud-decisions topic, it can use the original transaction_id as the message key. Downstream consumers of fraud-decisions (e.g., the Authorization Service or the database consumer) must also be designed to be idempotent.

- Database-Level Idempotency:

- When the database consumer attempts to insert a transaction into PostgreSQL, it leverages the transaction_id (or idempotency_key) with a UNIQUE constraint.

- The INSERT … ON CONFLICT (transaction_id) DO NOTHING; or INSERT … ON CONFLICT (transaction_id) DO UPDATE SET … statement ensures that if the same transaction is attempted to be inserted multiple times (e.g., due to a Kafka re-delivery), the database operation is either ignored or updates the existing record without creating a duplicate. This provides strong “exactly-once” semantics for the effect of the operation on the database.

- Transactional Outbox Pattern (Advanced): For complex scenarios where a microservice needs to atomically update its own database and publish a Kafka message, the transactional outbox pattern ensures consistency. The message is first written to an “outbox” table within the service’s database transaction. A separate process then reads from this outbox table and publishes messages to Kafka. This ensures that either both (DB update and Kafka publish) succeed, or neither does.

8.2 Retry and dead-letter queue (DLQ) patterns

- In-Process Retries with Exponential Backoff: For transient errors (e.g., temporary network glitches, Redis timeout), microservices implement internal retry logic with exponential backoff. This prevents immediate re-attempts from overwhelming a potentially recovering dependency. Libraries like tenacity in Python can be used.

- Kafka Retry Topics: If an error persists after a few in-process retries, the message is sent to a dedicated “retry topic” (e.g., fraud-events-retry-1m, fraud-events-retry-5m). These topics are consumed by separate consumer groups configured to wait for a specified delay before re-processing. This frees up the main consumer group to continue processing other messages.

- Dead-Letter Queue (DLQ): After exhausting all retry attempts (e.g., fraud-events-retry-final), messages are moved to a fraud-events-dlq topic.

- Purpose: To isolate “poison pill” messages that cannot be processed due to fundamental data issues or bugs.

- Monitoring: The DLQ is constantly monitored. Alerts are triggered when messages land in it.

- Manual Intervention: Operations teams can inspect messages in the DLQ, debug the root cause, fix the data or code, and manually re-submit them if appropriate, preventing service disruption.

8.3 Graceful degradation and circuit breakers

- Circuit Breakers: Implement circuit breakers (e.g., using Hystrix equivalents like pybreaker for Python) around calls to external dependencies (e.g., third-party risk APIs, or even internal Redis/DB if they show severe instability).

- How it works: If a dependency consistently fails or becomes slow, the circuit breaker “trips,” short-circuiting subsequent calls to that dependency for a period. Instead of waiting for a timeout, the system can immediately return a fallback response (e.g., a default “approve” or “review” decision if a risk API is down) or use cached data. This prevents cascading failures and allows the system to continue operating, albeit with potentially reduced functionality or accuracy.

- Bulkheads: Partition resources (e.g., thread pools, connection pools) for different services or types of requests. This prevents a failure or overload in one area from consuming all resources and affecting other parts of the system. For example, dedicating separate Redis connection pools for velocity checks versus blacklist lookups.

- Graceful Degradation: When a non-critical component fails or slows down, the system should ideally degrade gracefully rather than fail entirely. For example, if a secondary data enrichment service (e.g., device fingerprinting) is unavailable, the Fraud Detection Service can proceed with the primary rules and make a decision based on available data, potentially flagging the transaction for later review if crucial data is missing.

8.4 Multi-region replication and disaster recovery

For mission-critical financial systems, disaster recovery is paramount:

- Active-Passive or Active-Active Deployment:

- Active-Passive: A primary region handles all traffic, with a secondary region on standby. Data is replicated asynchronously (e.g., Kafka MirrorMaker for topics, PostgreSQL streaming replication) to the passive region. In a disaster, traffic is failed over to the passive region.

- Active-Active: Both regions actively serve traffic. This requires careful consideration of data consistency and conflict resolution, especially for stateful components like Redis and PostgreSQL.

- Kafka Geo-Replication: Kafka MirrorMaker (1.0 or 2.0) or Confluent Replicator can be used to replicate Kafka topics asynchronously between clusters in different data centers or cloud regions. This ensures that event streams are available in the disaster recovery site.

- PostgreSQL Replication: Streaming replication (physical or logical) provides continuous data replication from the primary to standby databases in other regions. This allows for rapid failover with minimal data loss.

- DNS Failover: Global DNS services (e.g., AWS Route 53, Google Cloud DNS) are configured to route traffic to the healthy region’s API Gateway in case of a regional outage.

- Regular DR Drills: Periodically performing disaster recovery drills is crucial to validate the failover procedures and recovery times.

8.5 Chaos testing and resilience validation

- Chaos Engineering: Proactively inject failures into the system (e.g., terminate random pods, introduce network latency, overload a Kafka broker) in a controlled environment to uncover weaknesses before they cause outages in production.

- Tools: Chaos Mesh, LitmusChaos (Kubernetes-native tools), or custom scripts.

- Purpose: Validate that retry mechanisms, circuit breakers, and autoscaling policies work as expected under adverse conditions. This builds confidence in the system’s resilience and helps refine operational playbooks.

9. Alternative Architectural Approaches

While FraudShield’s event-driven, microservice-based architecture is optimized for real-time, high-throughput fraud detection, it’s important to understand alternative approaches and why they might not be ideal for this specific problem.

9.1 Batch processing model (Spark/Flink) — why it’s not ideal for real-time fraud

- Description: In a batch processing model, data is collected over a period (e.g., hours), then processed in large chunks. Tools like Apache Spark or Apache Flink (in batch mode) excel here, performing complex aggregations and computations over historical data.

- Why not ideal for real-time fraud:

- High Latency: The inherent delay in batch processing (minutes to hours) means that by the time fraud is detected, the fraudulent transaction has often already completed, and funds may be irretrievable. This is unacceptable for modern payment systems.

- Limited Responsiveness: Cannot react instantly to emerging fraud patterns.

- Not Actionable: Decisions are retroactive rather than preventative.

9.2 Streaming ML pipelines (Kafka Streams / Flink / Faust)

- Description: This approach involves building real-time machine learning inference pipelines directly on streaming data. Instead of a rule engine, an ML model continuously consumes events, extracts features, performs predictions, and publishes fraud scores.

- Advantages:

- Higher Accuracy: ML models can detect complex, non-obvious fraud patterns that rule engines might miss.

- Adaptive: Can adapt to new fraud patterns as models are retrained.

- Real-time: Can deliver predictions with very low latency.

- Why not the only approach for FraudShield:

- Complexity: Building and maintaining real-time ML pipelines (feature stores, model deployment, monitoring model drift) is significantly more complex than a rule-based system.

- Explainability: “Black box” ML models can be harder to explain to regulators or customers, whereas rule engines offer clear, auditable logic.

- Cold Start: ML models require historical data for training and may not perform well on completely new fraud patterns until retrained.

- FraudShield’s Stance: This is a strong future enhancement (Section 11.1), not the initial core. A rule engine provides a solid, auditable foundation, which can be augmented by ML.

9.3 Serverless fraud detection (AWS Lambda + Kinesis)

- Description: Utilizing cloud-native serverless services. For example, AWS Kinesis for streaming, AWS Lambda for processing functions, DynamoDB for state, and API Gateway for ingestion.

- Advantages:

- High Scalability: Cloud providers handle infrastructure scaling automatically.

- Pay-per-Execution: Cost-effective for intermittent or unpredictable workloads.

- Reduced Operational Overhead: No servers to manage.

- Why not FraudShield’s core choice (initially):

- Vendor Lock-in: Tightly coupled to a specific cloud provider’s ecosystem. FraudShield aims for more cloud-agnostic deployment flexibility.

- Latency Variability: Lambda cold starts can introduce latency spikes, which can be critical for sub-500ms fraud decisions unless provisioned concurrency is used (which negates some cost benefits).

- Debugging Complexity: Distributed tracing and debugging can be more challenging across numerous serverless functions.

- Cost at Scale: While cheap for low usage, extreme high-throughput, continuously running serverless functions might become more expensive than well-optimized, always-on containerized services for sustained workloads.

9.4 Event sourcing and CQRS-based design

- Description: